Last Updated: 07/05/2025

Lymphoma in Dogs: Causes Symptoms Diagnosis and Treatment

Learn all about the causes symptoms diagnosis and treatment of lymphoma in dogs.

Author: Dr Nicole du Plessis BVSc (Hons)

Reading Time: 54 minutes - long read

What is Lymphoma??

Lymphoma is a group of diverse cancers with more than 30 different types of lymphoma described in dogs. It arises from a type of white blood cell called lymphocytes, which when healthy are involved in vital immune functions. Canine lymphoma can affect almost every part of the body, but frequently affect the lymphoreticular system. This includes lymph nodes, lymphatic vessels, bone marrow, the thymus and the spleen.

How Common Is Lymphoma In Dogs?

Breeds predisposed to lymphoma:

Many popular breeds have a genetic predisposition for developing lymphoma. Doberman, Rottweiler, Australian Cattle Dog, Boxer and Bernese mountain dogs are amongst the listed breeds. Boxers tend to develop T-cell lymphomas (either high- or low-grade) while Rottweilers have a high prevalence of B-cell lymphomas.

Higher incidence of lymphoma are found typically in breeds such as Bullmastiffs, Basset hounds, St. Bernards, Scottish terriers, Airedales, Pitbulls, Briards, Irish setters, German Shepherds, Labradors and Bulldogs.

What Causes Lymphoma In Dogs?

Despite lymphoma being one of the most common cancers in dogs, the cause remains unlear. Over the years, many risk-factors have been studied. The use of lawn care herbicides such as 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid have been examined, with a potential increased risk with exposure. Dogs who live in areas with high levels of electromagnetic fields have been examined with a weak to moderate risk identified, especially for dogs that spend the majority of their time outdoors. Other potential links have been explored, ranging from certain bacteria, viruses, and skin conditions such as atopic dermatitis. Unfortunately, no direct cause has been linked to the development of this diverse group of cancers and it is most likely multifactorial.

As canine lymohoma shares similarities with Non-Hodgkins Lymphoma in humans, immune suppression has been proposed as a risk factor of developing lymohoma. This is extrapolated from human studies, where lymphoma patients have significantly suppressed immune function. Definitive evidence that immune suppression causes canine lymphoma has not been confirmed.

Symptoms Of Lymphoma In Dogs?

Lymohoma can be difficult to detect, especially in the earlier stages of the disease. As it can affect many different body systems, it has many different presentations. Some signs of lymphoma are very subtle or non-specific. There are several different types of lymohoma in dogs:

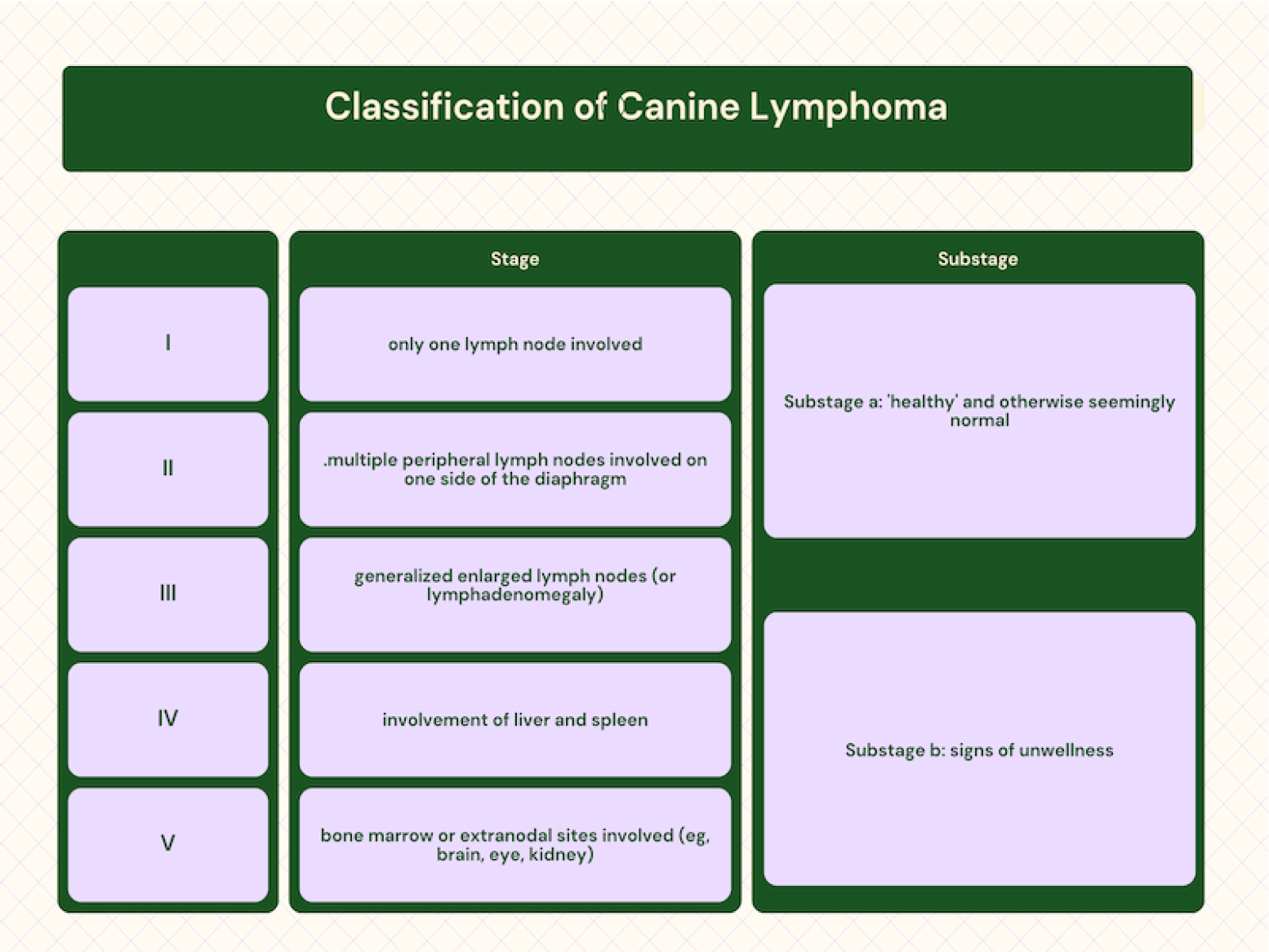

Generalized or Multicentric: this form of lymphoma will often present with enlarged peripheral lymphnodes at various sites; submandibular lymph node found under the jaw, prescapular lymohnode in front of the shoulder blades and popliteal lymph node behind the knees. Most dogs will be seemingly healthy, unless they fall into the 10-20% of dogs who have substage b (see staging for lymphoma). Other symptoms that may be present include a reduced appetite, weight-loss, lethargy and occasionally an increased thirst and urination.

Alimentary or Gastrointestinal: this form of lymohoma relates to the gastrointestinal tract. It can present with relatively non-specific signs such as vomiting, diarrhoea, weight-loss and reduced appetite.

Cutaneous: the 'great imitator' of lymphoma. This form of lymphoma can have a wide variety of lesions, from skin to oral. It may or may not cause itching for the dog and can vary from a peculiar-appearing rash to large nodular tumours.

Mediastinal: relating to the thorax, this form of lymphoma tends to present with respiratory signs. These signs can be overt, such as difficulty breathing, or muffled heart sounds that can be detected during a chest examination.

Symptoms of lymphoma noticed at home:

- Enlarged lymph nodes: The most common sign of lymphoma in dogs is the presence of swollen lymph nodes, which can often be felt as lumps under the skin, particularly around the neck, shoulders, groin, and behind the knees.

- Increased thirst and urination:Certain types of lymphoma produce a hormone called PTH-rp (parathyroid hormone related protein) leading to hypercalcaemia, too much calcium in the blood stream. This can lead to drinking more water than usual and needing to urinate more frequently.

- Gastrointestinal symptoms:Lymphoma can also affect the digestive tract, leading to symptoms such as vomiting, diarrhoea, or abdominal pain.

- Loss of appetite:Dogs with lymphoma may experience a decrease in appetite or may refuse to eat altogether. This can lead to weight loss and a decrease in energy levels.

- Lethargy: Dogs with lymphoma may appear tired or lethargic, showing a lack of interest in activities they previously enjoyed.

- Difficulty breathing: In some cases, lymphoma can affect the lungs, causing difficulty breathing or coughing.

- Skin changes: In rare cases, lymphoma may manifest as lumps or lesions on the skin.

- Ocular signs: Occasionally lymphoma can cause uveitis which may make the white part of the eye look red, and the eye appear cloudy.

- Fever: Dogs with lymphoma may develop a fever, although this symptom is not always present.

Image Credit: Purdue University Veterinary College of Medicine

How To Diagnose Lymphoma In Dogs?

The mere discussion of lymphoma can come to a shock to owners, especially if the dog was brought to the vet for a completely unrelated reason. Although canine lymphoma may be suspected during a physical examination, there are a number of diagnostic steps prior to being able to definitively diagnose lymphoma.

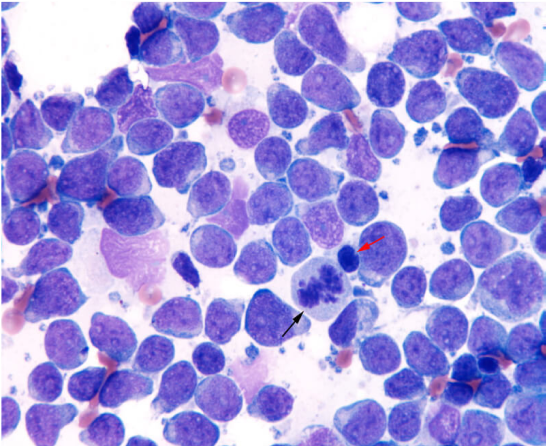

Fine needle aspirate: is a simple procedure, which takes cells from an area of interest where the veterinarian or pathologist can examine the cells under the microscope. In the case of large-cell lymphoma in dogs, a fine needle aspirate can yield enough information for a diagnosis. In the case of small-cell lymphoma, it can be more difficult to identify cancerous cells from normal lymphocytes.

Biopsy: is taking a larger section of tissue for histopathology and sending away to an external laboratory. A fine needle aspirate will not always give clear results, especially in suspected cases of small-cell lymphoma, a biopsy can give a more accurate result. The trade-off is that a biopsy is a more invasive procedure and will require heavy sedation or a general anaesthetic. In some cases, an entire lymphnode will be removed for confirmation.

These are diagnostics that can help your veterinarian reach the diagnosis of canine lymphoma. Other questions still remain that can alter prognosis and treatment. This is where staging becomes important, how far has the cancer spread? To answer this, additional diagnostic tests and imaging is required. This can also help establish a baseline for monitoring response to treatment, if that is the direction chosen for the dog.

Abdominal Ultrasound: considered a minimally invasive procedure, it can give valuable diagnostic information regarding appearance of abdominal organs like the spleen, liver and abdominal lymphnodes. All are areas of concern when lymphoma is suspected. If organ enlargement is found in the liver or spleen, fine needle aspirates can be taken at this time.

Chest radiographs (X-rays): mediastinal lymphoma is found in the chest cavity, so this is an area of interest. Chest x-rays are helpful in assessing the structures within the chest, as well as looking at any other potential co-morbidities that could affect prognosis, such as heart disease.

Blood test: a complete blood count, biochemistry (including blood calcium levels) and thyroid levels are ideal. Blood testing is simple and can be repeated to monitor response to chemotherapy. Blood testing is important from the beginning as it can help factor into prognosis. Dogs with elevated calcium levels are more likely to have T-cell lymphoma, which carries a worse prognosis.

Urine test: used to screen for any upper or lower urinary tract issues. Kidney function is important to monitor during chemotherapy. Urinary tract infections can become a problem for dogs with a suppressed immune system.

CT scan and/or MRI: more advanced imaging is sometimes called upon, especially if brain or organ metastasis is suspected.

Bone marrow biopsy: in more advanced stages of lymphoma, there can be bone marrow involvement. A bone marrow biopsy is considered a more invasive procedure than a peripheral lymphnode biopsy but, in some cases, necessary to perform.

Immunophenotype, is it B-cell or T-cell Lymphoma?

Approximately two thirds of large-cell lymphomas are B-cell, while the remaining unlucky one third of dogs will have large-cell T-cell lymphoma. As T-cell phenotype spells a poorer prognosis with generally shorter median survival times, this highlights the importance of identifying the phenotype. It can also help your veterinary oncologist choose the most appropriate treatment, since both B-cell and T-cell lymphoma will respond to different chemotherapy protocols. Your veterinarian may order the following tests to help confirm the immunophenotype: immunohistochemistry, immunocytochemistry, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), such as the PARR and flow cytometry.

Immunohistochemistry or immunocytochemistry is the use of special stains to assess for certain cell markers to allow differentiation between different types of lymphoma. Most commonly this is used to help us to differentiate between B and T cell intermediate or large cell lymphoma. This test is only used after a diagnosis of lymphoma has been made.

Flow cytometry:

this test assesses for particular cell characteristics to help to determine different types of lymphoma, as well as diagnosis of certain other blood borne cancers such as leukemia. Similarly to immunohistochemistry and immunocytochemistry, this test is not used on its own; it is used once a diagnosis of lymphoma has already been made.PCR for antigen receptor rearrangement (PARR): both samples from a fine needle aspirate and biopsy can be used for this diagnostic test to help differentiate between small cell lymphoma and other diseases. PARR can help identify if the cell population has arisen from the same mutated cancerous cell. If the result is that the cell population is clonal (from the same cell), this can help support the diagnosis of lymphoma. It must be interpreted alongside physical examination findings and other diagnostic information. The sensitivity and specificity of a PARR is reported to be 75 to 85% and 92 to 94% respectively; however, it is generally not a frequently performed test.

Image courtesy Today's Veterinary Nurse. Ultrasound image of a liver with suspected lymphoma involvement.

Image courtesy of eClinPath. Cytology consisting of large lymphocytes.

What Is The Treatment Of Lymphoma In Dogs?

The main treatment for most types of lymphoma is chemotherapy. Cancer cells were once normal cells that have mutated and multiply unchecked until the pet succumbs to the illness. Chemotherapy is administered to attack these uncontrolled, rapidly multiplying cancer cells. When chemotherapy is administered to kill cancer cells, unfortunately healthy rapidly dividing cells will also be affected. Generally, the rapidly dividing cells are found in the bone marrow, hair follicles, and gastrointestinal tract, so the side effects experienced are often related to these systems.

Chemotherapy objectives do differ with humans and pets. A more aggressive chemotherapy approach in humans results in more severe side effects compared to what we see in pets. In human medicine, chemotherapy aims to try to eliminate the cancer altogether and prevent reoccurrence, whereas in pets the goal is to improve quality of life. This is not to say that the goal of remission isn't possible. Some cancers, including lymphoma, can respond very well to chemotherapy.

There are a wide range of chemotherapy drugs and applications in veterinary medicine. The most appropriate treatment protocol can depend on the type of cancer involved. Interventions can include the use of surgery, radiation and chemotherapy. In the case of lymphoma, types will respond positively to different treatments. Lymphoma is a cancer that does respond well to combination chemotherapy drugs, with remission rates between 80 and 90%.

B-cell lymphoma: the most common treatment deployed for this type of multicentric lymphoma is the CHOP protocol. This is a combination of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone. It is typically administered over 11 to 25 weeks, depending on the response seen and the variation of CHOP protocol used. Owners should expect to invest a large amount of time and money in veterinary visits, as these treatments are administered weekly. There will be repeated blood and urine tests to continue to monitor the response to the chemotherapy and to look for signs of toxicity to any of the drugs used.

Doxorubicin is occasionally used as a sole chemotherapeutic agent. It is generally used in three week intervals for 5 weeks and with this can reduce costs associated with treatment. The median survival time will not always be comparable to CHOP-based protocols and fewer patients are expected to respond to single agent therapy. It does not reduce the cost of diagnostics and progress visits, which are still a vital part of the treatment plan.

T-cell lymphoma: most common chemotherapy protocols used are CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) or LOPP which consists of lomustine, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisolone. Single agent therapy with a chemotherapeutic called lomustine may also be utilised.

It is important to note that the chemotherapy protocol can vary depending on the treating oncologist, overall health of the pet and response to treatment. Although initial response rate is usually good, it is important to note that T-cell lymphoma does have lower median survival times and shorter remission times when compared with B-cell lymohoma.

If chemotherapy is not an option to treat canine lymphoma, what medications are available? Prednisone which is a steroid, often used to reduce the symptoms of lymphoma, and make the dog as comfortable as possible. Unfortunately, this does have the lowest response rate and shortest survival time compared to multi-agent and single agent chemotherapy. It is important to note that if this option is chosen, it will be difficult to achieve the same outcome if chemotherapy is chosen at a later date. This is because Prednisone is more likely to induce drug-resistance to the chemotherapy. Recent studies have assessed radiation therapy as a component of therapy for lymphoma, along with chemotherapy, with promising results.

What Is The Prognosis Of Lymphoma In Dogs?

Multicentric lymphoma in dogs is a cancer that has good response rates to chemotherapy. The goal of treatment is complete remission, which eliminates the symptoms of lymphoma, while also preserving a good quality of life for the dog. Canine lymphoma treatment can achieve complete remission rates up to 95%; however, this will only be temporary. Unfortunately, lymphoma will return despite chemotherapy. Treatment can be administered again, but generally remission will be shorter the second time around.

Dogs who have undergone multi-agent chemotherapy for B-cell lymphoma usually live an average of 12 months. This reduces to 25% of dogs surviving past 24 months. The survival time for dogs who have undergone multi-agent chemotherapy for T-cell lymohoma usually live an average of 6 to 8 months. Some dogs will go on to live far longer than the average and some will sadly pass away sooner than the average survival time. A number of factors can affect this such as the overall health of the dog, and the presence of any other co-morbidities such as heart disease or kidney disease

Chemotherapy is the main treatment for canine lymmphoma. Other medications can be used to help keep the dog comfortable for a short time. Prednisone alone may extend survival time for 2 to 3 months. Without any intervention lymohoma moves quickly, sadly most dogs will not live past 1 month after diagnosis.

Further Reading

Want to read more? Check out our other articles:

References:

This article was written with contributions from Dr. Sophia Wyatt BVSc (hons I) MANZCVS Small Animal Medicine.

- Lymphoma in Dogs & Cats: What's the Latest? | Today's Veterinary Practice

- Canine Lymphoma Research - College of Veterinary Medicine - Purdue University

- Canine Lymphoma - WSAVA 2017 Congress - VIN

- Lymphoma in Dogs - Veterinary Partner - VIN

- Breed-associated risks for developing canine lymphoma differ among countries: an European canine lymphoma network study

- Retrospective study on the occurrence of canine lymphoma and associated breed risks in a population of dogs in NSW (2001-2009)

- The Pet Oncologist - Vet Cancer Education

- Household Chemical Exposures and the Risk of Canine Malignant Lymphoma, a Model for Human Non-Hodgkinâs Lymphoma

- Residential Exposure to Magnetic Fields and Risk of Canine Lymphoma

- Classification of canine malignant lymphomas according to the World Health Organization criteria

- Lymphoma in Dogs - Melbourne Veterinary Specialist Centre

- Canine lymphomas: association of classification type, disease stage, tumor subtype, mitotic rate, and treatment with survival

- Predictors of long-term survival in dogs with high-grade multicentric lymphoma

- What Affects Survival Time and Life Expectancy for Dogs with Lymphoma?

- What is the Best Protocol for Canine Lymphoma?

- Efficacy and tolerability of a 12-week combination chemotherapy followed by lomustine consolidation treatment in canine B- and T-cell lymphoma

- Randomised trial evaluating chemotherapy alone or chemotherapy and a novel monoclonal antibody for canine T-cell lymphoma: A multicentre US study

- Immunophenotyping with Canine Lymphoma | VETgirl Veterinary CE Blog

- Lymphoma in Dogs (Canine Lymphoma, Lymphosarcoma in Dogs)

- Withrow and MacEwen's Small Animal Clinical Oncology. Book - Sixth Edition - 2020

Want to know more? Check out our Discover Page for more tips on keeping your pets happy and healthy.